![Tanuki Possession Mizuki Shigeru]()

Translated and Sourced from Mizuki Shigeru’s Mujyara, The Catalpa Bow, Myths and Legends of Japan, Occult Japan, Japanese Wikipedia, and Other Sources

There are eight million gods and monsters in Japan, and more than a few of them like to ride around in human bodies from time to time. Yurei. Kappa. Tanuki. Tengu. Kitsune. Snakes. Cats. Horses. Almost anything can possess a human. But when they do, they are all known by a single name—Tsukimono, the Possessing Things.

What Does Tsukimono Mean?

Tsukimono is a straight forward term. It combines the kanji憑 (tsuki; possession) +物 (mono; thing). There is a different word for actual possession憑依 (hyoi), which is the kanji 憑 (tsuki again, but this time pronounced hyo—because Japanese is hard) + 依 (I; caused by).

Although they are collectively known as tsukimono, different types of tsukimono use –tsuki as a suffix, such as kappa-tsuki (河童憑; kappa possession), tengu-tsuki (天狗憑; tengu possession), or the most common of all, kitsune-tsuki (狐憑; fox possession).

(憑 is an odd kanji by the way. It can do double duty not only as the verb tsuku (憑く; to possess) but also as a kanji for tanomu (憑む; to ask a favor). So in a strange way, possession means asking a favor of someone—really, really hard.)

Shinto God Possession

![Kami Possession Mizuki Shigeru]()

Spirit possession is an ancient and ubiquitous belief in Japan. In his 1894 book Occult Japan, Percival Lowell wrote:

“The number of possessing spirits in Japan is something enormous. It is safe to say that no other nation of forty millions of people has ever produced its parallel….”

Probably the most ancient form of the phenomenon is God Possession. There have long been mediums who could voluntarily drawn the power of kami or ancestor spirits into their bodies to serve as oracles. As in many spiritual traditions, the medium goes into a trance and clears their mind so that the kami can enter. The medium is just an empty vessel that gives voice to the kami.

The kami can be singular or plural, an ancestor spirit or merger of deities. Because of the obscure nature of the kami and their relation to the sorei ancestor spirits, it can be hard to tell. As Lowell says, “In Shinto god-possession we are viewing the actual incarnation of the ancestor spirit of the race.”

However, this kind of God Possession—known alternately as kamiyadori (神宿り; kami dwelling), kamioroshi (神降ろし; kami descending), or kamigakari (神懸り; divine possession) –is different from tsukimono.

Tsukimono – Yokai and Animal Possession

Tsukimono are almost exclusively yokai or animal spirits invading human bodies. This is rarely a spontaneous event—often the yokai possesses the human as an act of revenge, for when a human kills one of the yokai’s children, or destroys it’s home, or something along that lines. Or it could be simple greed, like a fox who wants to eat a delicious treat that it normally can’t get it’s paws on. The reasons are as innumerable as the yokai themselves. But as opposed to the Shinto God Possession, it is always involuntary on the part of the possessed. No one invites a tsukimono into their body.

![Mizuki_Shigeru_Kappa_Tsuki]()

The effects of the possession vary widely as well. In most possessions the victim takes on the attributes of the yokai or animal. A victim of tanuki-tsuki (tanuki possession) is said to voraciously overeat until their belly swells up like a tanuki, causing death unless exorcized. Uma-tsuki (horse possession) can cause people to become ill-mannered, huffing at everything and sticking their face into their food to eat like a horse. Kappa-tsuki become overwhelmed with the need to be in water, and develop an appetite for cucumbers.

In general, the only way to free someone from a tsukimono is through an exorcist. Usually these were the wandering Shugendo priests called Yamabushi. They were the great sorcerers and exorcists of pre-modern Japan, roaming through the mountains and coming down when called to perform sacred services and spiritual battles.

Types of Tsukimono – Snakes, Foxes, and Everything Else

The types of tsukimono change depending on who you ask, and when. The great Meiji-era folklorist Yanagita Kunio split tsukimono into two distinct types, snakes (hebi-tsuki) and foxes (kitsune-tsuki).

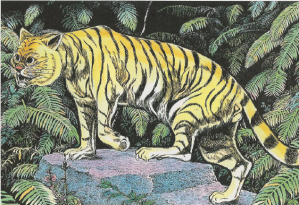

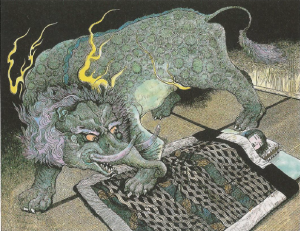

The snake was found primarily in Shikoku, and went by various names. Hebigami (蛇神; snake god), Tobyo or Tonbogami. As you can see by the name, these snakes were not typical snakes, but where thought to be snake gods with the ability to possess humans. In many descriptions they do not even resemble snakes, but are more like great earthworms.

![Tonbogami_Mizuki_Shigeru]()

What Yanagita referred to as a kitsune was quite different from the usual fox. It was a small, four-legged furry creature that resembled a weasel or shrew more than anything else. The kitsune also went by regional various names, like ninko (人狐; human fox) or yako (野狐; field fox). The animal roamed over Kansai, Kanto, and Tohoku districts. Whatever the animal was called in the local vernacular, the description given was always the same; a distinctly non-foxlike animal that every called a fox.

Yanagita was quick to put the name kitsune to all 4-legged animal possessors. He linked the kitsune-tsuki to one of Japan’s other great possessing animals, the inugami (犬神; Dog God), that moved throughout Shikoku and Chugoku districts.

Very few folklorists agree with Yanagita’s fox/snake categories. Most who write on the subject have seen much, much more variety in tsukimono. Percival Lowell wrote:

“ … there are a surprising number of forms. There is, in short, possession by pretty much every kind of creature, except by other living men.”

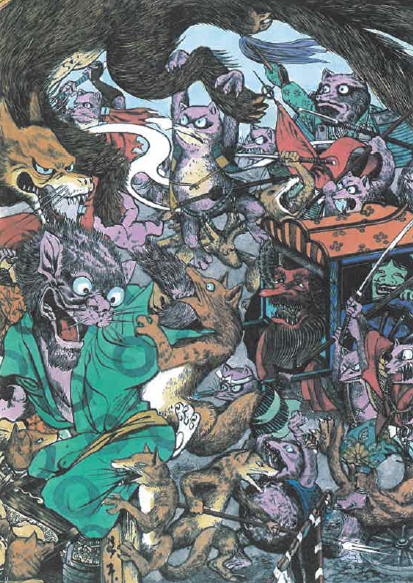

Mizuki Shigeru agrees with Percival Lowell. In his Mujyara, series he identifies the following types of possession. It is is by no means meant to be a complete list:

• Jizo-tsuki – Possession by Jizo

• Kappa-tsuki – Kappa possession

• Gaki-tsuki – Hungry Ghost possession

• Tengu-tsuki – Tengu possession

• Shibito-tsuki – Ghost possession

• Neko-tsuki – Cat possession

• Hebi-tsuki – Snake possession

• Tanuki-tsuki – Tanuki possession

• Hannya-tsuki – Hannya possession

• Ikiryo-tsuki – Living Ghost possession

• Uma-tsuki – Horse possession

• Inu-tsuki – Dog possession

• Kitsune-tsuki – Fox possession

Kitsune-tsuki and Kitsune-tsukia – Fox Possession and Fox Users

![Gyokuzan_Kitsunetsuki]()

Kitsune-tsuki is by far the most common type of tsukimono. It is also different from other tsukimono—instead of the possessed taking on fox-attributes, kitsune-tsuki feels like a bodily attack, with shortness of breath, phantom pains, speaking in strange voices, and epileptic fits. Kitsune-tsuki symptoms resembled classic demonic possession in Western culture.

Up until WWII, kitsune-tsuki in particular was treated with deadly seriousness, by both mystics and scientists. F. Hadland Davis wrote in his 1913 book Myths and Legends of Japan:

“Demonical possession is frequently said to be due o the evil influence of foxes. This form of possession is known as kitsune-tsuki. The sufferer is usually a woman of the poorer classes, one who is highly sensitive an open to believe in all manner o superstitions. The question of demoniacal possession is still and unsolved problem, and the studies of Dr. Baelz of the Imperial University of Japan, seem to point to the fact that animal possession in human beings is a very real and terrible truth after all. He remarks that a fox usually enters a woman either through the breast or between the finger-nails, and that the fox lives a separate life of its own, frequently speaking in a voice totally different from the human.”

Another huge different with kitsune-tsuki is that, instead of the possession being the will of the yokai, it could be a deliberate attack. A breed of sorcerers known as kitsune-tsukai (Fox Users) were said to have invisible kitsune at their command, and could send them to possess people at will. This could also be for any reason, from revenge to profit. A particularly devious type of extortionist kitsune-tsukai would send their kitsune to possess someone, then appear in the guise of an exorcist to drive the spirit out—for a fee, of course.

![Fox_Possession_Japan]()

Kitsune-tsukai gain power over their familiars in what is known as the Izuna-ho, or Izuna rite. The complete ritual is laid out in the 17th century Honcho Shokkan; find a pregnant fox and feed her and tame her. When she gives birth, take special care of her cubs. When her cubs are strong enough, she will eventually come and ask you to name one as thanks. With that done, the fox you named is under your control, and will respond to the power of its name. Continue to feed the fox, and you are know a Kitsune-tsukai. You can ask it questions that it must answer, or send it to perform your nefarious deeds.

A hallmark of the kitsune-tsukai is that they were the nouveaux riches—people of poverty who suddenly gained wealth and property. There was no possible explanation for the sudden rise in status of these people other than they had a magical, invisible fox at their command.

One strange aspect of kitsune-tsukai is that—along with the dog-possession called inugami—it is thought to be hereditary. Becoming a kitsune-tsukai taints your entire line, and from that time forward invisible foxes will hang around the houses of your ancestors. You are now part of a tsukimono-tsuji, a witch clan.

Kitsune-tsukai and tsukimono-tsuji were actively discriminated against. It was a taint that lasted forever, and people would carefully check the family background of potential marriage or business partners to ensure that they had no hint of kitsune-tsukai lineage. To bind your family to a tainted family was disastrous—you and all your heirs would now carry the taint. During the Edo period in particular people were vigilant against kitsune-tsukai. Accused families would be burned out of their homes and banished.

With no surprise, kitsune-tsukai discrimination is often linked to burakumin discrimination. Many burakumin families were accused of being kitsune-tsukai, and people said that when you walked through a burakumin village you could see the invisible foxes haunted the houses, waiting for their master’s commands.

Predjudice against tsukimono-tsuji and kitsune-tsukai families lasted well into the 1960s when human rights laws were enacted forbidding discrimination against them. To this day, however, I am sure you can find a few people who would be shy to marry or do business with a known kitsune-tsukai.

Translator’s Note:

This article was done for Brandon Seifert, who does the incredibly cool comic Witch Doctor![]() . Is there a yokai-inspired comic in Seifert’s future? I suggest you keep an eye out on your local comic shop!

. Is there a yokai-inspired comic in Seifert’s future? I suggest you keep an eye out on your local comic shop!

I feel like I may have bitten off more than I can chew with this article—it started out as a simple explanation of tsukimono, but soon expanded into much, much more. And even this is just a glimpse; there is much more to tell about tsukimono, kitsune-tsukai, and the various other forms of possession than I can fit on this blog. Hopefully this will serve as a solid overview. Time permitting, I will do individual articles on the different types of possession in the future.

For now, anyone interested in learning more should check out The Catalpa Bow: A Study in Shamanistic Practices in Japan. The chapter on tsukimono—or Witch Animals—is available online here.

Further Reading:

For more stories of possessing yokai and snakes, check out:

Inen – The Possessing Ghost

The Tanuki and the White Snake

The Snake’s Curse

![]()

from Drawn & Quarterly.

from Drawn & Quarterly. (also from Drawn & Quarterly) I gained a new appreciation of Nezumi Otoko. Just like Donald Duck and Wimpy from Popeye, Nezumi Otoko plays an important role in Gegege no Kitaro, and it is easy to see why he is Mizuki Shigeru’s favorite.

(also from Drawn & Quarterly) I gained a new appreciation of Nezumi Otoko. Just like Donald Duck and Wimpy from Popeye, Nezumi Otoko plays an important role in Gegege no Kitaro, and it is easy to see why he is Mizuki Shigeru’s favorite.

. Is there a yokai-inspired comic in Seifert’s future? I suggest you keep an eye out on your local comic shop!

. Is there a yokai-inspired comic in Seifert’s future? I suggest you keep an eye out on your local comic shop!